There still are some clock sellers and buyers who mistakenly believe that "Breveté" is a French clock brand name.

It isn't.

Breveté (or brevete without the accent as most sellers write it) means patented in French and most clocks produced between about 1850 and 1950 have that word stamped on the back....It is the legal registration of some element of the clock or all of it.

Along with breveté, SGDG is usually also stamped on the back case of a French clock produced during that period.

SGDG is not a brand.

It means 'Without any guarantee from the Government' (Sans Garantie Du Governement) and was by law required to be stamped on ALL objects with a legal patent from 1844 until 1968, especially those manufactured for export.

Some French manufacturers produced clocks for high-end jewellers (such as Tiffany's, Mappin Webb and private names) without stamping their own brand name on them, BUT they did have to stamp "Breveté" and SGDG somewhere on the movement and usually on the back case.

Some manufacturers also made their export clocks easier to identify by stamping "Made in France" or simply "France" rather than Fabriqué en France on them. It is not that unusual to find two identical models of a clock, one with Fabriqué en France on it which means it was made for the French market and the other with Made in France which was exported.

ART DECO clocks

This blog is about clocks, mostly French manufacturers created between 1920 and 1940. In it, I'll be talking about the most famous French manufacturers of the period - DEP, Duverdrey & Bloquel (Bayard) Blangy, Jaz, SMI, "Just" and some others...if there is any interest, I can also date most clocks quite accurately

Monday, March 4, 2013

Thursday, August 30, 2012

JAZ Commemorative clock

This particular clock is easily recognizable by the number "70" printed on the dial in a small rectangle and the brand name Jaz under the 12 with the bird's tail in a downward position. The overall styling is very "Art Deco" with honeycomb hands, a 'skyscraper' styling, rectangular brass decorations on the front and the elongated dial face.

The movement is a quartz operated on a small battery. Quartz movements were not incorporated into clocks until the 1970's and basically meant the end of mechanical movements. In comparison to its predecessors, this clock is relatively very light in weight.

Although it is a relatively recent issue, it has become over the past decade a very collectible piece, however it should not be confused with JAZ bakelite cased clocks manufactured in the 20's and 30's.

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

JAPY Frères clocks

There are so many JAPY clocks still around because Frederic Japy (1749-1812) was one of the founders of the industrialization of not only clocks, but of manufacturing in general. An imaginative inventor of all sorts of machines, he began his career as a watchmaker. At that time, watch and clock parts were manufactured usually by hand by specialized workers in their homes in small communities.

There are so many JAPY clocks still around because Frederic Japy (1749-1812) was one of the founders of the industrialization of not only clocks, but of manufacturing in general. An imaginative inventor of all sorts of machines, he began his career as a watchmaker. At that time, watch and clock parts were manufactured usually by hand by specialized workers in their homes in small communities.

The parts were then collected and mounted into a piece by an 'assembler'. Once the movement was assembled, it was then sent to a 'dresser' who would in turn mount it into a case - be it a small one or an elaborate brass plated mantle clock complete with mythological figures.

Frederic Japy purchased some of few clock making machines in existence, brought them back to his native town of Beaucourt and proceeded to invent new ones in order to standardize the pieces and the quality of the production.

The workers were then regrouped into one location instead of being scattered throughout the countryside and each one was assigned to a specific work post with its own specific machine. Frederic Japy radically changed the way clocks were produced. The sequential production of parts in one location - a manufacturing plant - aided by machines meant that clock parts were made and assembled in about half the time that it had taken previously.

Japy's plant revolutionized manufacturing. Production schedules were now established by the plant owner and not by the local artisan. The number of steps and operations were reduced by half. All parts could be assembled into a finished product on-site instead of the previous sub-assemblies and the machines could be operated by a less-skilled worker.

Japy then imagined other applications (and invented the machines required to produce them) such as the mass production of hardware parts (screws, nails, bolts) and other products - rotating pumps (a model still in use today), locks, and he perfected the creation and baking of enamelware.

In clockmaking - Japy's enamel dials became the standard for the great majority of clock manufacturers for 150 years both in France and abroad. There are few French carriage clocks in existence that do not have Japy enamel dials on them.

Japy's plants continued to produce clocks in many styles and at the higher priced levels. In 1806, he handed the direction of his businesses to his three sons - and it became Japy Frères (Japy Brothers) who in turn diversified the manufacturing to produce coffee grinders, typewriters, enamelware, kitchen utensils, office machines such as the first typewriters, refrigerator pumps, advertising signs and they invented more machines to transform copper and steel wires into elaborate hardware parts.

However, his sons' sons did not inherit the creative and inventive spirit of their fathers and grandfather and by the early 1900's, many of the the businesses were sold off and the manufacturing was dismantled.

A classic Japy Frères clock from the late1890's with the well-known logo and the announcement of having won the 1878 Grand Prize for clockmaking.

A classic Japy Frères clock from the late1890's with the well-known logo and the announcement of having won the 1878 Grand Prize for clockmaking.

ALL Japy clocks - large or small are signed either on the back case and/or stamped on the movement.

In the 1930's, Japy Frères decided to 'reinvent' themselves to appeal to a wider market and they produced several models with tin casings and in various geometrical styles. Unfortunately they were competing with names such as Jaz and Blangy in that segment of the market and sales were rather limited. As with most French clockmakers, WWII basically decimated them

|

| 1932 ad in la France Horlogère advertising Japy's new line of alarm clocks. |

After the war, the name brand Japy was sold off to another clock manufacturer who mass produced cheap models of alarm and desk clocks.

Saturday, August 4, 2012

How it got started

My interest in French art Deco period clocks began with a small, tarnished brass DEP clock bought in a flea market. I cleaned the case to a shiny brilliance and then plunked the dirty movement in a special clock cleaning fluid and left it there overnight. 80 years of old oil, dirt, nicotine and coal dust oozed to the bottom of the dish. I wound it up and lo and behold, it began ticking. I was hooked.

My interest in French art Deco period clocks began with a small, tarnished brass DEP clock bought in a flea market. I cleaned the case to a shiny brilliance and then plunked the dirty movement in a special clock cleaning fluid and left it there overnight. 80 years of old oil, dirt, nicotine and coal dust oozed to the bottom of the dish. I wound it up and lo and behold, it began ticking. I was hooked.

During the past nine years, I've done a lot of research on DEP clocks as well as on the majority of French clock manufacturers. As my personal collection grew, I met dozens of equally passionate clock collectors, attended clock fairs, dug up old papers, catalogues and histories, visited clock museums and had the priviledge of meeting the late Georges Lacroix who owned the greatest DEP clock collection in existence. A true renaissance man, Georges not only generously shared his collection but also introduced me to the descendants of the original DEPery family. Interestingly, Georges' father and grandfather were also clockmakers and worked in the DEP manufacturing plants.

What has always intrigued me about clocks is how such functionally mundane object could be interpreted so many different ways - especially the dials and numbering.

There are thousands of clock collectors in the world, each of them with their own special interest and clock fairs bring out the best of them and there is no doubt that we all roam the aisles and happily discuss our collections, always in the hope of finding that one clock that we don't have yet.

So happy hunting to each and every one of you.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

Charles Hour - Diette Hour - Hour Lavigne and "JUST" clocks

Charles Victor HOUR, one of the co-founders of HOUR LAVIGNE which still produces some of the finest and most spectacular clocks today (Google Hour Lavigne) began as an apprentice at 11 years of age. Twenty years later, he bought out a failing manufacture and in 1891 took on an associate - Diette. Together they became one of the most important clock makers in France.

Hour then associated himself with Maurice Lavigne and by the end of the XIX C, Hour Lavigne was the largest clock and timepiece manufacturer in France with over 800 employees.

|

| Carriage clock with DH stamped on movement |

DIETTE HOUR (D.H.)

During the years of association with Diette, most of the models produced reflected the styles and taste of the period, including small carriage clocks with a visible escapement and balance wheel. They had DH stamped on the back of the movement and were delivered in very fine calf leather carrying cases.

|

| CH HOUR rectangular carriage clock |

Their more popular models included enamel dial clocks that were incorporated into large bronze or porcelain mantle clocks such as the one shown below.

Their clocks were entered in numerous exhibits and won the Grand Prix in Brussels in 1910 and the Grand Prix in Turin in 1911.It was very important for a clock maker's reputation and sales to be present in the various exhibitions and to win since clocks were an expensive domestic object and those who could afford them tended to prefer the cachet conferred by the manufacturer who had won the Grand Prize and could advertise the win on the back of the clock case.

After WWI, Hour Lavigne revolutionized the concept of what a clock could look like. While most manufacturers interpreted the new Art Deco movement as using existing clock movements and dials in more stylized casings, Hour Lavigne transformed all visible parts of a clock - the dial, the case, the hands, the numbering into a new, coherent whole truly reflective of the Art Deco style. At the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, they presented a dozen clocks that simply wiped out the competition.

|

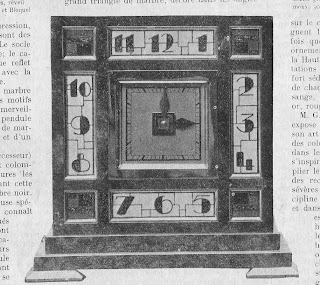

| Photograph from La France Horlogere of 1925 showing the winning exhibition Hour Lavigne clock. |

One of the most striking examples presented by Hour Lavigne at the 1925 Art Deco Exhibit from the catalogue. The clock case is in red veined marble while the numbers are small tablets of white fired enamel with the numbers in red encrusted in them. Four small stylized squares with small gold frames fill the corners while the black hands reflect the round chubbiness of the font used in the numbering on a gold background. A judge described it as a symphony of red, white and black worthy of the highest admiration.

The Hour Lavigne clocks shown in 1925 redefined the aesthetics of clockmakers for decades. While many of their pieces were 'one of' (as most Art Deco pieces were before mass reproduction), they had shrewdly realized after WWI that there was a growing market for high quality, original clocks reflecting the new streamline Art Deco aesthetics. That resulted in the extension of the "JUST" brand which had been used for their watch production since the 1900's, to clocks.

While they kept up the production of their more traditional mantle clocks and large bronze ornament clocks with garnitures and figures, they developed a new line of regulator clocks and smaller clocks based on the success of the the clocks they had presented at the 1925 Exhibition.

One of those clocks is shown on the left. Most of the large JUST clocks from that period were manufactured in very limited numbers as they were relatively expensive and very heavy (this one is over 10 lbs in weight) to ship.

The clock on the left has an asymmetrical case composed of three different colours of marbles with a polished chrome face and short, square shaped hands.

The numbering is unique and original in that it is one of the few clocks that did not use Roman numerals as do the great majority of JUST clocks.

During this period, they also manufactured clocks that were stamped with the brand name of some of the most prestigious jewellers such as Tiffany & Co.

High-end jewelers in both America and in the U.K.did not normally manufacture the clocks they sold under their names, but sought out prestigious clockmakers to produce models with their brands stamped on the dial and the maker's name or logo on the movement.

During the 1920's and 1930's they also produced many models of small easel clocks and two or three function clocks (a clock plus a barometer and a thermometer and a calendar).

Two of the small easel clocks produced in the mid 1920's. Their clocks were mostly decorative with no alarm function.

Two of the nine models of easel clocks with triple functions ( clock + calendar + thermometer). These models were frequently stamped with the name of a jeweler and the location of the shop. The movement is that of a pocket watch. The calendar days were stamped on a roll of thin tissue and suffered the greatest wear. Dates were stamped directly on the brass plate.

Two of the nine models of easel clocks with triple functions ( clock + calendar + thermometer). These models were frequently stamped with the name of a jeweler and the location of the shop. The movement is that of a pocket watch. The calendar days were stamped on a roll of thin tissue and suffered the greatest wear. Dates were stamped directly on the brass plate.

While they kept up the production of their more traditional mantle clocks and large bronze ornament clocks with garnitures and figures, they developed a new line of regulator clocks and smaller clocks based on the success of the the clocks they had presented at the 1925 Exhibition.

|

| "JUST" clock 1930 |

The clock on the left has an asymmetrical case composed of three different colours of marbles with a polished chrome face and short, square shaped hands.

The numbering is unique and original in that it is one of the few clocks that did not use Roman numerals as do the great majority of JUST clocks.

During this period, they also manufactured clocks that were stamped with the brand name of some of the most prestigious jewellers such as Tiffany & Co.

High-end jewelers in both America and in the U.K.did not normally manufacture the clocks they sold under their names, but sought out prestigious clockmakers to produce models with their brands stamped on the dial and the maker's name or logo on the movement.

During the 1920's and 1930's they also produced many models of small easel clocks and two or three function clocks (a clock plus a barometer and a thermometer and a calendar).

Two of the small easel clocks produced in the mid 1920's. Their clocks were mostly decorative with no alarm function.

The most popular JUST models aside from the more traditional ones, were brass case easel clocks.

Two of the nine models of easel clocks with triple functions ( clock + calendar + thermometer). These models were frequently stamped with the name of a jeweler and the location of the shop. The movement is that of a pocket watch. The calendar days were stamped on a roll of thin tissue and suffered the greatest wear. Dates were stamped directly on the brass plate.

Two of the nine models of easel clocks with triple functions ( clock + calendar + thermometer). These models were frequently stamped with the name of a jeweler and the location of the shop. The movement is that of a pocket watch. The calendar days were stamped on a roll of thin tissue and suffered the greatest wear. Dates were stamped directly on the brass plate.

Some of the brass easel clocks included a barometer as well as a calendar and thermometer.

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

BAYARD Carriage clocks

When Albert Villon established his clock making shop in 1867 in St Nicholas D'Aliermont in northern France, he specialized in marine clocks and travel/carriage clocks.

During the next decades, the company changed names - from Duverdrey & Bloquel to Bayard and made many models of clocks -including traditional carriage clocks with solid brass cases and bevelled glass fronts, sides and backs and several models also had visible escapements.

In 1978 Bayard was taken over by Jaeger-Levallois from Switzerland.

In the 1980's (1982-83) they began reproducing some of the clocks that had originally been manufactured by the first Bayard company, including a line of 'mignonettes' - carriage clocks.

Mignonettes (meaning small, sweet i.e. mignon) are excellent, high-class reproductions of some of the carriage clocks made by Duverdrey & Bloquel at the beginning of the XIXth Century. They are still mechanical clocks (not quartz) and should not be confused with Bayard carriage clocks made in the XIXth or early XXth centuries.

A total of four different mignonette models were produced, some with Arabic numbers, other with Roman numerals. All have solid brass cases, bevelled glass fronts, backs and sides and an 8-day movement with an enamel dial.

They measure 82 x 147 mm and weigh about 630 grams.

They are easily recognizable by the name 'Bayard' stamped on the dial below the 12 along with 8 day and Made in France.

Most of them were made and sold for export to the UK and the US.

Another indication that it is a 'mignonette' is that the back plate of the clock has "7 seven (or 9 nine) jewels/unadjusted/Duverdrey & Bloquel/France/ and a series number engraved on it.

They are becoming more and more collectable since their production ceased thirty years ago and their mechanical movement is of the same high quality as the original Bayard carriage clocks. The 'mignonette' model with Arabic numbers is the rarest of the four models.

During the next decades, the company changed names - from Duverdrey & Bloquel to Bayard and made many models of clocks -including traditional carriage clocks with solid brass cases and bevelled glass fronts, sides and backs and several models also had visible escapements.

In 1978 Bayard was taken over by Jaeger-Levallois from Switzerland.

In the 1980's (1982-83) they began reproducing some of the clocks that had originally been manufactured by the first Bayard company, including a line of 'mignonettes' - carriage clocks.

|

| Bayard Migonette |

A total of four different mignonette models were produced, some with Arabic numbers, other with Roman numerals. All have solid brass cases, bevelled glass fronts, backs and sides and an 8-day movement with an enamel dial.

They measure 82 x 147 mm and weigh about 630 grams.

They are easily recognizable by the name 'Bayard' stamped on the dial below the 12 along with 8 day and Made in France.

Most of them were made and sold for export to the UK and the US.

Another indication that it is a 'mignonette' is that the back plate of the clock has "7 seven (or 9 nine) jewels/unadjusted/Duverdrey & Bloquel/France/ and a series number engraved on it.

They are becoming more and more collectable since their production ceased thirty years ago and their mechanical movement is of the same high quality as the original Bayard carriage clocks. The 'mignonette' model with Arabic numbers is the rarest of the four models.

Saturday, April 9, 2011

JAZ - the success of the 1930's

As early as 1924, Jaz began exporting clocks not only to other clock producing countries in Europe, but also to the Americas and to the Far-East. As its reputation grew, so did the number of models as well as technical improvements of the mechanical movements. Until 11930, most of its clock models were round clocks in brass, chrome or small square ladies clocks in the same materials.

Then in the early 1930's, aa new material came onto the market that would revolutionize manufacturing: Bakelite. As Jaz preferred to customize its components, it named the bakelite used in its model Jazolite. Coinciding with new casings was the new major technical advancement of an 8 - day movement to replace the 30 hour movement. New clocks now only required winding every week instead of every day.

New alarm clock models began filling the shelves and Jaz strongly promoted the idea of a clock in every room in the house including the kitchen.

Then in the early 1930's, aa new material came onto the market that would revolutionize manufacturing: Bakelite. As Jaz preferred to customize its components, it named the bakelite used in its model Jazolite. Coinciding with new casings was the new major technical advancement of an 8 - day movement to replace the 30 hour movement. New clocks now only required winding every week instead of every day.

New alarm clock models began filling the shelves and Jaz strongly promoted the idea of a clock in every room in the house including the kitchen.

|

| Berric model 1935 |

|

| Lotic model 1934 |

|

| Lorric Model 1937 |

|

| Persic model 1938 |

|

| Lucic Model 1935 |

Every model produced came in different dials, with luminous or non luminous hands but the same finish that could be kept pristine with a simple wipe of a cloth.

In 1934 they produced a large mantle sized clock using a new type of movement that was almost silent and did not include an alarm . The Silentic had something unique: a tiny triangle in the 12 indicating that the clock needed to be wound when it showed red.

|

| Gotic model 1931 |

|

| Janic model 1934 |

|

| Romic model 1931 |

While bakelite was widely used in a large selection of clocks, other materials (brass, chrome and porcelaine) continued to be utilized in an ever expanding line of models.

The Romic (left) was one of the most popular models. Its use of shiny chrome, the semi-circular design, the 'beehive' hands and the luminous numbers appealed to the Art Deco style.

With its expanding markets, Jaz began print advertising and to distinguish it from its competitors, most of its ads were in black and red on a white background.

Jaz was the leader in the number of styles, models and overall sales until WWII, when materials became rarer and workers were drafted into military service.

Until 1941, all Jaz clocks had the word JAZ stamped on the dial above the 6.

When the Third Reich invaded France, the Nazis objected to the use of the word JAZ because it was interpreted as a symbol of 'decadent American music'. To circumvent their objection (and possible closure of the production plants) the directors explained that the name JAZ referred to a small bird, the Jaseur Boréal and bore no relation to the music. As a result, all clocks manufactured after 1942 had a little bird stamped above the Jaz name. The bird's tail was directed downward and this was used until 1967, when the bird's tail was then directed upward.

After 1975, the bird disappeared and the name JAZ now appeared under the number 12.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)